Genre: Shoot-’em-up

Number of Players: 1-2 (Alternating)

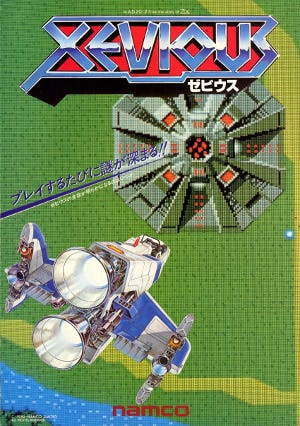

Developer: Namco

Publisher: Namco (JP), Atari Inc. (US)

Release Date: December 1982 (JP), February 1983 (US)

Platform: Arcade

Also Available On: Apple II, Atari 7800, Atari ST, NES, Famicom Disk System, Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, X68000, ZX Spectrum, Game Boy Advance, PlayStation, PS4, Nintendo Switch

Whenever I play the arcade version of Xevious, I often think back to the moment I discovered the game. It was sometime in 1993 or so. Back then, our family couldn’t afford such luxuries as a Super NES or Sega Genesis. So a friend of ours gave us her Atari 7800, along with a trash bag full of games, out of the pity generosity of her heart.

Unlike us, she could afford to purchase the Sega Genesis, meaning the 7800 was just collecting dust until she handed it down to us. While rummaging through the multitude of Atari cartridges in the days ahead, I came across Xevious. The name and cover art intrigued me, so I decided to fire it up and see what’s what. I was not disappointed.

I was fascinated by the unique enemy designs and mysterious land structures peppered throughout the game. Years later, after delving into websites dedicated to retro gaming, I was surprised to learn that Xevious was more than just a forgotten title on a defunct Atari console. It was a trailblazer, one of the most popular and innovative arcade games of its time.

In a 1985 interview, the game’s designer, Masanobu Endo, revealed his vision to create "a consistent world and setting, high-quality sprites," and "a story that could stand on its own merits." When it was released internationally in 1983, Xevious defined the vertical-scrolling shoot-’em-up genre, earning its place in the pantheon of historically significant games.

If you’ve ever read the story elements of this game, then you already know that Xevious spins a tale rife with twists and turns. So I’ll do my best to keep it simple. A war breaks out between humans and the General Artificial Matrix Producer (GAMP)—a machine they created capable of mass-producing human clones.

The GAMPs grew tired of humans using them for joyless slave labor. So they rebelled, vacated Earth, and traveled to the planet Xevious, where they hatched a plot against humanity. Thousands of years and one ice age later, the GAMPs return to Earth to enslave humans and take over the planet. It’s up to you to pilot the Solvalou ship and defend Earth against its would-be conquerors.

The core design elements of Xevious outpaced those of arguably every other shooter that came before it. It went a few steps further than just blasting the same set of bug-like creatures off the screen. You had two separate weapons: the Zapper, dedicated to destroying aerial enemies, and the Blaster—an unlimited supply of bombs for taking out ground bases and vehicles with the help of a targeting reticle in front of your ship.

Having separate weapons for aerial and ground enemies introduced new layers of strategy and complexity. As attacks from enemies increase, pursuing every enemy on the screen may not always be advantageous. As a result, you’ll often need to choose the best course of action under rapidly changing circumstances.

Xevious brimmed with personality. It was full of nuances that weren’t seen in vertical-scrolling shooters at the time. The aerial enemies have intricate designs and realistic attack patterns, compared to other games of the time. Previously, in fixed-screen shooters like Space Invaders, enemies marched in the same simplistic pattern. Or in games like Galaxian and Galaga, the space bugs were constantly doing kamikaze dives, attempting to crash into your ship. But in Xevious, enemies will swoop in to fire a quick shot and peel away once they cross your ship’s flight path.

It was a deliberate design choice by Endoh because he knew that in real life, it wouldn’t make sense for fighter pilots to crash into an enemy plane as a general strategy. Even if that line of reasoning never crossed your mind when playing the first few times, you could still tell that something was different about this game in how the enemy ships reacted to your presence. A subtle design choice gave Xevious a sense of plausibility in an era when such details were largely overlooked.

In total, there are 16 different sections in the game. Dense forest areas mark the boundary between each section. Some areas culminate in a battle with the Andor Genesis—an imposing mothership that can only be destroyed by dropping a bomb into the core reactor in the center of the ship. It is considered to be one of the earliest examples of an end-level boss in a scrolling shooter.

It seemed like there was always something new being thrown at you. Whether weaving through indestructible spinning monoliths, avoiding shrapnel released from exploded bombs, or flying over the Nazca lines etched in the ground below, there was plenty to see in Xevious.

This game also features one of the earliest examples of adaptive difficulty. As your efficiency at destroying enemies increases, new swarms appear with behaviours different from the standard enemies you fought in the opening moments of the game. Aggressively destroying everything in your path causes the game to retaliate by increasing its difficulty. It was a unique feature that created a varied and unpredictable experience.

As you progress further into the game, ground enemies also behave differently. Seemingly innocuous targets earlier in the game suddenly start firing bullets at you. Tanks that were initially motionless suddenly become mobile to outmaneuver your blaster bomb.

Interestingly, some ground targets never pose an immediate threat but can still be destroyed. Of particular note is the Zolback ground unit—a small dome with four red blinking marks. While they cause you no harm, they serve as radar installations that give away your position to the enemy. Failing to destroy the radar units increases the aerial forces attacking you. On the other hand, if you do manage to destroy them, the enemy's aggression will momentarily lessen.

Xevious is also one of the first games to have hidden bonuses. The most memorable ones for me are the hidden “S” flags from Rally-X, which are revealed by bombing certain terrain areas. Collecting a flag nets you either 10,000 points or a nifty 1-up (depending on the arcade dip switch setting); something you can never have enough of in this game.

You can also uncover secret Zol towers strewn about by using the same technique for finding “S” flags. Revealing a Zol tower nets you 2,000 points, and destroying it awards you an additional 2,000 points to your score. It’s a great way to quickly rack up the points needed for an extra ship.

My only criticism of Xevious is that your ship is a little too slow compared to the enemies’ bullets. It’s too easy to get caught in the crossfire if you’re not mindful of your position on the screen. Certain enemies have tricky flight patterns. They can be hard to evade when attacking in swarms.

It is especially troublesome to avoid bullets while flying over large bodies of water because the bullets blend in with the blue color and white dots used for the water graphics. It’s a real pet peeve of mine because, in those scenarios, I often find myself second-guessing where to position my ship, losing my concentration, and inevitably getting shot down. Not my preferred way to go.

The visual presentation in Xevious was quite unique for its time. Instead of an empty background or a simplistic star field, the action unfolds over an Earth-like landscape. You can easily distinguish between grassy, dirt, and forest terrain. The character pixels were rendered carefully using gray colors and palette shifting. Each enemy has smooth, realistic animations unlike anything seen in games before this one.

Arcade games running on the Namco Galaga system board were known for delivering high-quality audio, and Xevious was no exception. A realistic “BOOM” emits from destroyed ground targets. Perhaps most notably, the Andor Genesis mothership eerily hums as it drifts backward, firing a volley of bullets at your ship. The musical score is one of the earliest examples of a consistent tune that plays throughout the game. Admittedly, it’s highly repetitive and outdated by today’s standards, but it still pioneered the idea that later mushroomed into full soundtracks in future arcade shooters.

Many gameplay elements of Xevious would go on to serve as a template for future vertical and side-scrolling shooters that would become major hits. In some cases, sub-genres would be born from these elements, like Konami’s Twinbee series, which spawned the cute-’em-up genre. Taito would later use a similar method to even greater effect in its Ray series, replacing bombs with impressive swirling lasers. Countless other shooters followed Xevious’ lead by using familiar scenery that would resonate with the player.

While it may be too old-school for some, the forward-thinking game design can be appreciated by most shoot-’em-up aficionados. The original arcade version of Xevious remains reasonably easy to find, as it has been included in multiple Namco Museum compilations on nearly every major home console and handheld since the mid-90s. It’s a nice piece of gaming history to have in your collection.

The source of the interview with Masanobu Endo quoted in this article is shmuplations.com. It’s a fascinating read, which you can check out here.

This was a great review, I love how you layered in your personal interactions with the game throughout your life, makes it a much more engaging read.

Personally, I've never quite clicked with Xevious. My introduction to this genre was with more bullet hell style games, or the more colourful pop'n twinbee. I can recognise what the game did and what it meant, but it doesn't quite work for me today.